When it comes to Liverpool Football Club, it is impossible to talk about the modern version without mentioning Bill Shankly. In spite of the fact that the club itself was formed more than two decades before the Scot was even born, there is little doubt that he helped to make it into the powerhouse that we all know and love.

How the likes of Carlisle United, Grimsby Town and Workington must deeply regret not giving him whatever he wanted to stay as their manager, given the extent to which he completely changed Liverpool’s fortunes during his 15 years at Anfield.

The great Bill Shankly ❤️ pic.twitter.com/8uh6WDlz4R

— AndyJFT97 🔴⚪️ (@Andybrawn6) September 12, 2023

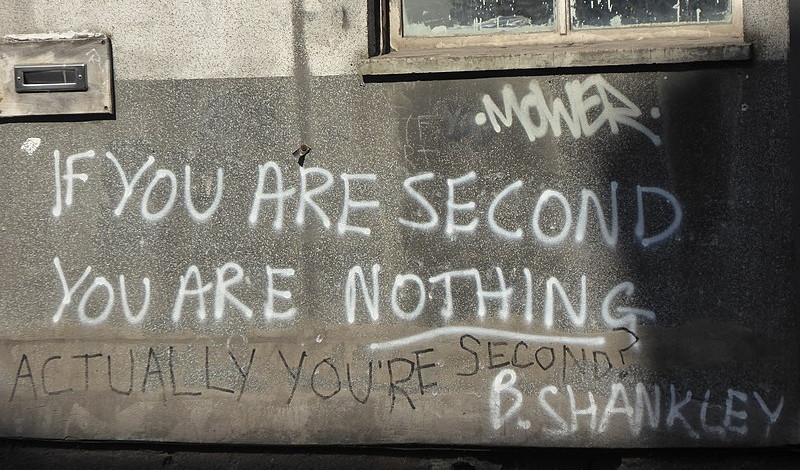

Even though Shankly left his role as manager of the Reds in 1974, there are very few aspects of Liverpool that don’t owe at least something to the manager. His statue stands outside of the Kop and the Reds run out the anthem that became theirs during the reign of Shankly. We have won league titles and domestic cups because of him, to say nothing of the fact that our European pedigree began during his time in the hotseat. Head to the ground and you’ll find pubs named in his honour in the local vicinity. In many ways, Bill Shankly was Liverpool Football Club.

Shankly’s Early Life

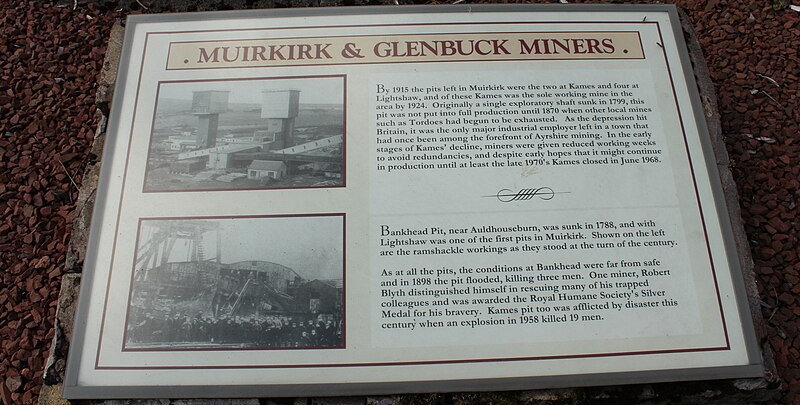

Born in the small coal mining village of Glenbuck in the Scottish country of Ayrshire, it wouldn’t have been unfair to think that Bill Shankly was destined to live his life as a miner. After all, there were only about 700 people living in the village on the second of September 1913 when Shankly was born. The main reason people left was to find work in larger mining towns, but certainly not to seek their fame and fortune. John and Barbara Shankly, Bill’s parents, lived in one of the Auchenstilloch Cottages and already had eight children when Bill came along, known as Willie to his family.

The youngest of the boys of the family, ‘Willie’ followed in the footsteps of his brothers by taking up football. Alec played for Ayr United and Clyde, whilst Jimmy made it to England and played for the likes of Sheffield United and Southend United. John had plied his trade for Portsmouth and Luton, with Bob gaining appearances for Alloa Athletic and Falkirk. Bob eventually went into management, winning Dundee United a Championship in 1962 and getting them to the semi-finals of the following season’s European Cup. The boys’ maternal uncles, Robert and William Blyth, also played football professionally.

In many ways, therefore, Bill was always destined to have a career involving football. When he wrote his autobiography he said that times were tough when he was young, often being hungry and struggling during the winter months. Along with friends, he would steal vegetables from nearby farms and bread and fruit from suppliers’ wagons. The discipline that he experienced at home and in school was tough, but ‘character-building.’ Even so, he played football whenever he could, even though there was no organised team at school. In 1928, he left school and worked at a local mine.

When the pit closed two years later, Bill faced unemployment and hoped that the fact that he’d played football so often might count for something. He would often go to see both Rangers and Celtic play in Glasgow, ignoring the sectarian divide. Football was eventually his salvation from unemployment, being signed by Carlisle United just a few months after losing his job when the pit closed. Having always believed that it was only a matter of time before he made his living as a footballer, Shankly was able to use the skills he’d learned playing with his brothers to do just that.

Shankly The Footballer

Carlisle United were relatively new to the Football League when Shankly played for them, playing their games in the Third Division North. He had been recommended to the club by a scout named Peter Carruthers, who had spotted him playing for a team called Cronberry Eglinton, based around 22 miles from Glenbuck. When he went for his trial, it was the first time that he had left Scotland and was signed after just one match for the reserves, in spite of the fact that they lost 6-0 in their match with Middlesbrough. He made his senior debut in the 31st of December 1932.

In total, he made 16 appearances for the first time, with the reserves defeating Newcastle reserves to win the North Eastern League Cup at the end of the campaign. He was considered to be a ‘hard running, gritty right-half.’ Paid what was considered to be a good wage of four pounds ten shillings a week at Carlisle, to say nothing of the fact that he was able to live close to home and liked his teammates. When the offer came to move on, therefore, he was less than convinced that it was the right thing for him to do. Even so, Preston North End had offered a fee of £500 to sign him.

Offered a fee of £50, a signing-on fee of £10 and a wage of £5 a week, Shankly was still not convinced until his brother Alec persuaded him that it was a good move to make. He started in Preston’s reserves, playing in the Central League, making his first team debut on the December of 1933. He created a goal early doors to help them beat Hull City 5-0. They gained promotion to the First Division at the end of the season, finishing as runners-up behind Grimsby Town.

He remained at the club until he retired as a footballer in 1949, having seen his wage increase to eight pounds a week and six pounds a week in the summer months, which was decent enough in those days.

He finished his career as a footballer having earned a reputation as tough-tackling half-back, considered to be as good as any other in the Football League. He joined the Royal Air Force when the Second World War broke out, meaning that he lost the peak years of his playing career, although he did manage to take part in some games during the war. Depending on where he was based, he ended up playing for the likes of Norwich City, Arsenal, Luton Town, Cardiff City, Lovell’s Athletic F.C and Partick Thistle, as well as a single game for Liverpool in 1942 – a 4-1 win over Everton at Anfield.

Bill Shankly 1938 on his Scottish debut, a 1-0 win against England. In a era where there wasn’t much international football he played 12 times for Scotland, 9 of them against the Auld enemy. @misshanks a great picture of your grandad pic.twitter.com/jW53xNyppd

— P O’Neill (@Big_Jim__Larkin) September 20, 2023

It wasn’t just club football that Shankly enjoyed. He made 12 appearances for Scotland between 1938 and 1943, with five of them being full internationals. He had ‘unbelievable pride’ to play for Scotland against the ‘auld enemy’ of England in his debut, helping the Scots to win 1-0 at Wembley. He also captained the Scotland team against England at Hampden Park in 1941, but the Three Lions won that match 3-1. He did manage to get on the scoresheet during the wartime match at Wembley, which Scotland won 5-4, linking up well with future managerial rival Matt Busby.

Moving Into Management

During his playing career, Shankly did what he could to absorb as much as possible from the managers that he played under. He looked at the various coaching systems that were used and believed himself to be a good leader. Having done the hard work, he waited for an opportunity to present itself, which it duly did when Carlisle United were struggling in the bottom half of the Third Division North during the 1948-1949 campaign. Shankly always said that he wanted players who had a combination of ability and courage, as well as fitness and a willingness to work.

When he took over at Carlisle, his work ethic helped the team to climb to 15th, improving to ninth the following year and then third in 1950-1951. One of the players that worked with him at Carlisle was Geoff Twentyman, a young centre-half who was later transferred to Liverpool. In the wake of his playing career, Twentyman became chief scout for the Reds, finding numerous excellent talents with Shankly once he’d begun managing at Anfield. One of his key attributes as a manager was to use psychology, often telling his players that the opposition were tired after a long journey.

In the end, Shankly’s time at Carlisle United came to a close when he accused the board of backing out of a promise to give the players a bonus if they finished in the top three. He resigned, taking up a role as the manager of Grimsby Town instead. When he left, he had led the club to 42 wins and 22 defeats from the 95 matches that he took control for. Interestingly, he did interview for Liverpool when he left Carlisle United but it didn’t go well, meaning that he was left to take up the role of manager of Grimsby Town instead, moving there in the June of 1951.

Having been relegated twice in the most recent seasons, dropping from the First Division to the Third, Shankly had his work cut out at his new club. The finished second to Lincoln City at the end of the 1951-1952 season, missing out on promotion because only one club went up at the time. He managed to get them to start the following season well, winning their first five games but eventually his ageing side finished fifth. In what had become something of a habit for the Scot, Shankly became disillusioned with the Grimsby board when they didn’t give him money for new players.

Having failed to promote from the reserves on account of loyalty to his senior players, Shankly eventually resigned from his managerial role in the January of 1954. He cited the lack of ambition of the board as the main reason behind his departure, admitting in his autobiography that he and his wife had become a little homesick. When he was offered a job at Workington, it was a move that he thought made sense because it would allow him to be closer to Scotland. He left Grimsby having notched up 62 wins and 35 losses from the 118 matches that he was manager for.

Shankly saw being the manager of Workington as a challenge, with the club sitting third from bottom of the Third Division North. He managed to get them up to 18th by the end of the season, keeping them in the division without the need to apply for re-election. The following season, they finished eighth and the attendances had risen from 6,000 to 8,000. Even so, the club operated on a shoestring budget and Shankly was needing to most of the administrative work himself. One of the biggest problems that he had was that the ground was shared with the local rugby league side.

Whilst he did have disagreements with the board, largely over the damage being done to the pitch by the rugby players, it wasn’t actually a falling out with them that caused him to leave. Instead, he resigned from his role as Workington manager in order to take up the role of assistant manager at Huddersfield Town alongside his friend Andy Beattie. He left Workington having won 35 games and lost 27 from 85 matches. Initially he worked as the reserve team coach at Huddersfield Town, being in charge of some promising youngsters before being promoted to the first team not long after.

Beattie resigned during the 1956-1957 season, with Shankloy being appointed as manager. Though he never managed to gain promotion as manager of Huddersfield Town, he did work with players like Denis Law, Ray Wilson, Les Massie and Bill McGarry. As had become something of a custom for him, he began to fall out with the Huddersfield Town board over the fact that they kept selling his best players without replacing them. Having seen his team beat Liverpool 5-0 with ten men, he was delighted when the Reds approached him to be manager in 1959. He left Huddersfield having won 49 and lost 47 of his 129 matches.

Shankly The Liverpool Manager

In 1959, the Liverpool Chairman, Tom Williams, called Bill Shankly and asked him if he’d like to manage the best club in the world. Shankly, tongue firmly in cheek, replied, “Why, is Matt Busby packing up?” He realised the potential at Liverpool, who were in the Second Division at the time, and accepted the manager’s job on the 14th of December 1959. The Reds had been in the Second Division for five years at that point, losing out in the FA Cup to non-league Worcester City. The stadium was in a state of disrepair, lacking the ability to water the pitch and needing thousands spent to fix it.

The team that Shankly took over was filled with average players, although there was some promise in the reserves. In spite of the problems, the Scot felt at home at Anfield and had an immediate connection with the supporters. He got a good relationship going with the coaching staff, with the likes of Bob Paisley, Joe Fagan and Reuben Bennett all working well with him and believing in the idea of loyalty. Shankly was a brilliant motivator, whilst Paisley was the tactician. The four converted an old storage room into what became known as the boot room, where tactical discussions took place.

Football History in Colour 🎨

Three of Liverpool’s Boot Room – Bill Shankly, Bob Paisley and Joe Fagan discuss tactics at Melwood. All three would manage the club during a period of unprecedented success. (1965)

Colourised: @Garswoodlatic pic.twitter.com/QBNrJ0mRB6

— The Football History Boys (@TFHBs) September 17, 2023

Whilst the coaches were excellent, Shankly said of the first team players, “After only one match I knew that the team as a whole was not good enough. I made up my mind that we needed strengthening through the middle, a goalkeeper and a centre half who between them could stop goals, and somebody up front to create goals and score them.”

He placed 24 players on the transfer list, with all of them having left the club within a year. He also worked to develop Melwood, the training ground, turning it from overgrown and weed-covered to a top-class facility.

Shankly and his coaches worked on training systems that would become the bedrock of Liverpool’s success, with the players eschewing long runs for training on grass with a ball. He introduced the five-a-side matches that had been important at his previous clubs, insisting that they were just as competitive as league games. He developed a routine designed to develop stamina, with the ‘sweat box’ seeing players go up against a small area for two minutes per session. Mainly, though, he turned to the transfer market to improve the Liverpool team.

He did have issues with the board, such as when he asked them to buy two Scottish players and was told that they couldn’t afford them. His ally on the board, Eric Sawyer, stepped in and said they couldn’t afford not to buy them. Those players were Ron Yeats and Ian St. John, who would go on to become stalwarts during Shankly’s time at the club. When Yeats, a centre-half, was signed, Shankly said to the press at the conference announcing his arrival, “go and walk round him; he’s a colossus!” Tommy Lawrence was promoted to the goalkeeper role from the youth team, giving Shankly his ‘strength through the middle.’

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FRERQ037xnQ

Jimmy Melia, Ronnie Moran, Alan A’Court, Gerry Byrne and Roger Hunt all being developed by Shankly at Anfield. His new team won the Second Division at the end of the 1961-1962 campaign, gaining promotion to the top-flight. The finished eighth in their first season back at the top, with the likes of Ian Callaghan, Tommy Smith and Chris Lawler being promoted out of the youth team. It led to Liverpool’s first top-flight title under Shankly and the sixth of the club’s existence, which was won at the end of the 1963-1964 campaign. Hunt believed that the key was Liverpool being the fittest team in the country.

Shankly’s long-term ambition had been to win the FA Cup, which was seen as being far more prestigious back then that it is by most people nowadays. The Reds won the competition for the first time in the club’s history when we defeated Leeds United 2-1 after extra-time in 1965, with Ian St. John scoring the winning goal. Shankly later admitted that winning it was one of his finest achievements in football. The Beatles had sent Shankly and his team a telegram before the FA Cup, whilst Shankly himself appeared on Desert Island Discs and picked You’ll Never Walk Alone as his eighth choice.

The club made its European debut the following season, reaching the semi-finals of the European Cup. It was in the second round tie that Shankly decided to change the Liverpool kit, moving from one that was red with white shorts and white socks to an all red kit, believing that it would make the players look taller. Initially, Liverpool only played in all-red for European matches, but it was soon adopted as the club’s permanent kit. The Reds might well have made the final of the European Cup, if not for controversy in the away leg that Shankly maintained was ‘war.’

Some stamps in the Bill Shankly’s passport, including one from Liverpool’s first ever game in the European competitions (away to KR Reykjavik in August 1964). pic.twitter.com/CL3yt9ac8a

— LFChistory.net (@LFChistory) September 15, 2023

In the years that followed, Shankly led Liverpool to three First Division titles, two FA Cups and the UEFA Cup, also being named Manager of the Year for the 1972-1973 campaign. In 1974, he was awarded the Officer of the Order of the British Empire. He was 60 when the club won the FA Cup in 1974, saying that he ‘felt tired’ when he got back to the dressing room. He decided that he could leave the club with his head held high, his only disappointment being that he didn’t win the European Cup. Having previously threatened to retire, Liverpool Secretary Peter Robinson was blasé about it initially.

When he realised Shankly was serious, however, he tried to get him to change his mind. He carried through with it, although regretted it almost immediately. He continued to turn up at the training ground, but eventually stopped when he felt that people were resentful of his being there. Some believe that he wanted a seat on the board in a similar fashion to what Busby had been offered by Manchester United, but it wasn’t forthcoming.

He died on the 29th of December 1981, being known as the father of modern day Liverpool and someone with countless brilliant quotes attributed to him.

Bill Shankly’s Honours List

Having ended his time as Liverpool manager with a win percentage of 51.98%, the trophies Shankly won during his career are as follows:

- Football League First Divisions: 3

- Football League Second Divisions: 1

- FA Cups: 3

- FA Charity Shields: 3

- UEFA Cups: 1